Something Fishy

Our pond has been frozen solid for months. Blanketed with snow for almost as long, it’s a stretch to remember how it appears in other seasons, when the dormant roses and river birch along its banks again fill with buds and blooms and birds; when the fish and frogs and turtles that somehow hibernate in its dark depths awaken and return to its rippling, glinting surface.

Our pond has been frozen solid for months. Blanketed with snow for almost as long, it’s a stretch to remember how it appears in other seasons, when the dormant roses and river birch along its banks again fill with buds and blooms and birds; when the fish and frogs and turtles that somehow hibernate in its dark depths awaken and return to its rippling, glinting surface.

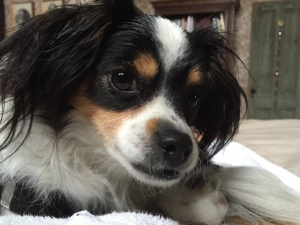

Willie seems to have no memory of that body of water beneath the snow. With the pond in this frozen and camouflaged state, Willie races right across it – following the straightest line between two points. From the sunroom, I watch him chase a terrified squirrel due west from the birdfeeders toward the pin oak near the beehives. Willie is as fast as the squirrel, and rockets after it with barely a foot between them. In that instant, I consider his weight, the thickness of the ice, the unknown depth of the pond. “Willie!” I call, clapping my hands. “Get off the pond! Come over here!”

The squirrel zips up the oak to the safety of its bare branches, and Willie turns to look at me. Then he sits down on the ice, appears puzzled.

“Willie!” I call again. “Come!”

My twelve-pound mutt, roughly the size of a housecat, makes the return trip across the pond with less enthusiasm and I wonder: What would I do, exactly, if he fell through the ice? How long before hypothermia pulled him under? What if I didn’t notice when the ice gave way? Should we have a life ring tethered to the shore? A pool skimmer? Should Willie ever be out here unsupervised during winter?

As temperatures moved up and out of single digits with the approach of spring, warmer days and a couple of rain showers dissolved much of the snow in our landscape, clarifying the pond’s borders and defining earth and not-earth. Looking out the windows the other morning I noticed some odd humps and bumps in the surface of the ice. I put on my jacket and hat and, with Willie at my heels, walked across the brown, frozen lawn toward the pond to investigate.

As temperatures moved up and out of single digits with the approach of spring, warmer days and a couple of rain showers dissolved much of the snow in our landscape, clarifying the pond’s borders and defining earth and not-earth. Looking out the windows the other morning I noticed some odd humps and bumps in the surface of the ice. I put on my jacket and hat and, with Willie at my heels, walked across the brown, frozen lawn toward the pond to investigate.

There, locked in the ice like an overturned boat, was the belly of a grass carp. And then I saw a catfish. And another. And over there, another carp breaking the surface with its side. All around the shoreline were dozens of sunfish and brown trout, like a scattered deck of cards, all frozen, all dead.

What happened? Some of these fish, like the carp and the cats that we put in this water ourselves, have survived more than twelve winters in this pond, growing to outsize proportions that sometimes shocked visitors. Why have all these fish died?

Back in the sunroom, Richard takes to his iPad. “Lack of oxygen,” he says finally, swiping through the screens. “That blanket of ice and snow basically suffocated them; it prevented the circulation of oxygen and blocked the sunlight the plants needed to make more. It says here it’s called a “winterkill” and that it’s most common in small ponds and lakes. It’s too bad.”

“It sure is,” I say, “And we’ll need more than a pool skimmer to remove all those fish before they start to reek and foul the whole pond.”

Richard puts on his coat and the three of us go back outside to further investigate. Willie circumnavigates the shoreline, sniffing, as Richard and I discuss what to do next.

“When it warms up a little more,” he says, “we can dig a big hole and bury them all somewhere.”

“And I’ll contact the D.E.C. to get some information about restocking.”

“And I’ll contact the D.E.C. to get some information about restocking.”

Without warning, while the two of us are standing there talking, Willie trots out onto the ice, grabs a small dead sunfish, and runs away with his treat.

“Willie! Come!”

With the humans in hot pursuit, this becomes a game. Willie drops the fish, lies on the grass, facing us, his prize between his paws. But as I close in, he picks up the fish and runs away again. “Willie, stay!” I command as I approach. I finally pick Willie up with my left hand and cradle him like a football. With two fingers, I pick up the fish by its tail. It’s lightweight and dessicated, as if it had been pressed between the pages of a book. Fish jerky.

We walk back toward the house, and when I think Willie is distracted, I stupidly flip the fish back out onto the ice, where it skitters and spins toward the center of the pond. With his powerful back legs, Willie then pushes off my ribs, leaping to the ground and racing back onto the ice for his fish. And so our game resumes. We travel around the pond a time or two, b ut Willie maintains enough distance between us to allow himself an occasional roll on the pond’s increasingly muddy banks. By the time I collect him and the sunfish – for a second time – he stinks.

ut Willie maintains enough distance between us to allow himself an occasional roll on the pond’s increasingly muddy banks. By the time I collect him and the sunfish – for a second time – he stinks.

“You’ve just earned yourself a bath, mister,” I say as we head back inside.

I’m sitting on a bench in the utility room toweling Willie dry when Richard appears in the doorway. “Come see this,” he says, motioning me to follow. When we sunroom windows come into view, he lifts his arm and points. “Vultures.”

There on the ice, and on the bank of the pond, are about dozen vultures and assorted crows, feeding on sushi. “Our clean-up crew is already on the job.”

Related Posts

-

New Routine

New Routine

The sun is coming up, and though I’m am early riser, it is not my habit to 03.03.2014.by edwillmatt@gmail.com -

Rainy Day Dog

Rainy Day Dog

After a long, dry spell during which the lawn browned, the tomatoes wilted, and the pond receded, last night 11.08.2015.by edwillmatt@gmail.com -

His Master’s Voice

His Master’s Voice

Willie didn’t make a sound for months after we first brought him home; not a whine or a growl 16.03.2015.by edwillmatt@gmail.com